-

Amidst the timeless expanse of geologic antiquity, some 480 million years ago, during the Appalachian mountain-building event during the Paleozoic Era within the Ordovician Period , bituminous coal was created by colliding land masses that compressed Carbon between sediment, rock, and soil.

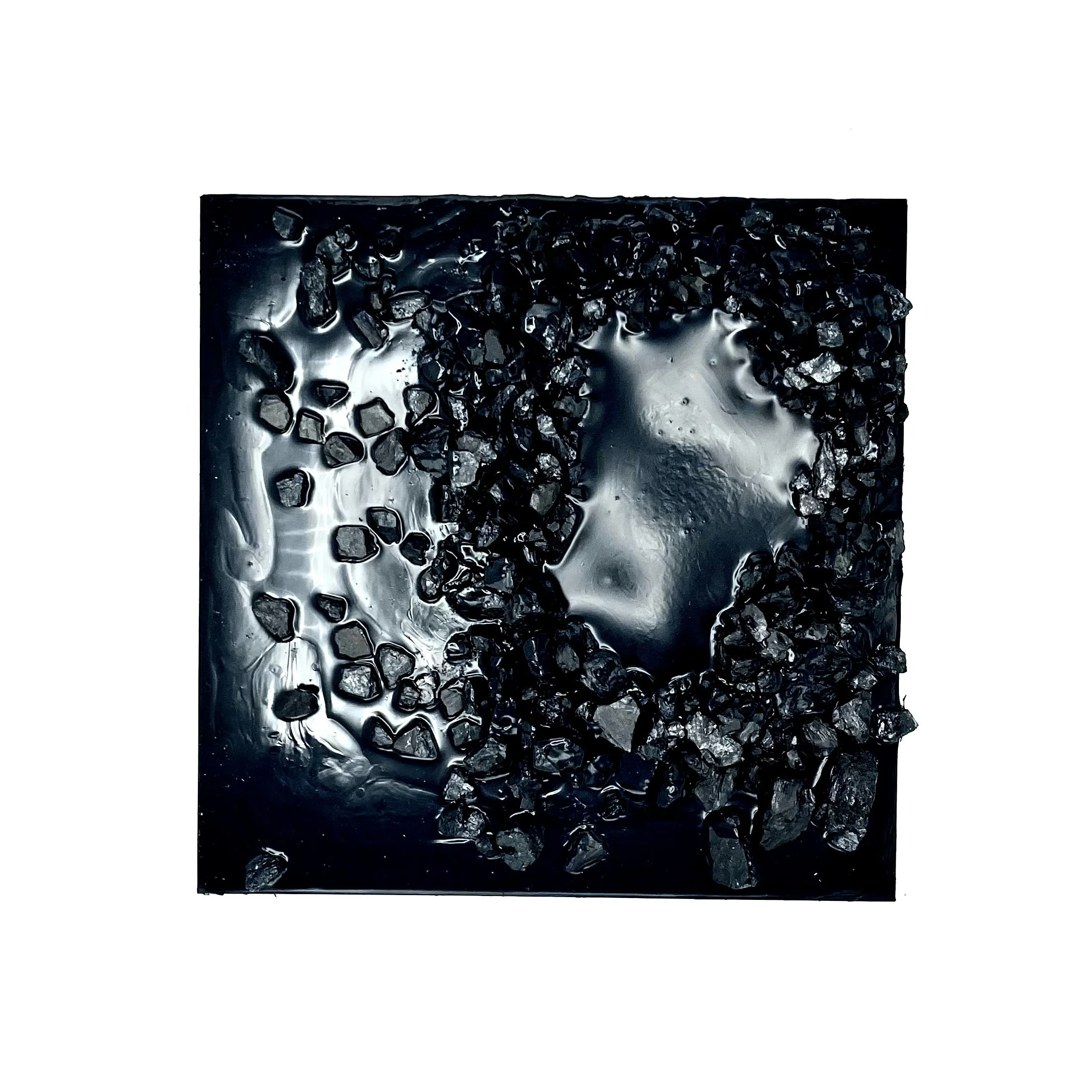

Here, a sculpted bituminous coal form rests upon a 20th century commercial proscenium. A gradient of surface treatments ranging from raw to fashioned fine finish.

Excavated from Eastern Kentucky in the United States of America.

-

Large and small seams of coal draw concentric circles upon reflective layers of gesturally foregrounded oil and tar. Operating as a vignettes of microscopic & monumental proportions, this material abstraction excavates questions of cyclical natures.

“I recall a kind of democracy of experience brought on by shared economic status and shared location. When we moved to the city, the sort of raising of our own social mobility was very tied to the increased contempt for poor white people. I have always wondered about the ways in which oppressed and exploited people can turn against people with whom we should stand in solidarity.”

bell hooks, 2019

-

Burning Issues (Excerpt):

“By the time coal mining really cut its chops as a fully fledged industry, industrial mining beckoned the interest of a new party: United States military weapons manufacturing. Thanks to neocolonialism, by way of the broad form deed, The United States energy industry now had a tried and true internal proof of concept. A record and system of capturing regions to extort laborers and natural materials. By systematically targeting susceptible communities on the outskirts of the nation, a now thriving American energy industrial complex could expand land seizure to build weapons. The market viability for militaristic involvement was primed and ready, and wielded assurances to extend the nation's energy profile.”

-Austin Casebolt

Petrified Light and Underground Heiresses

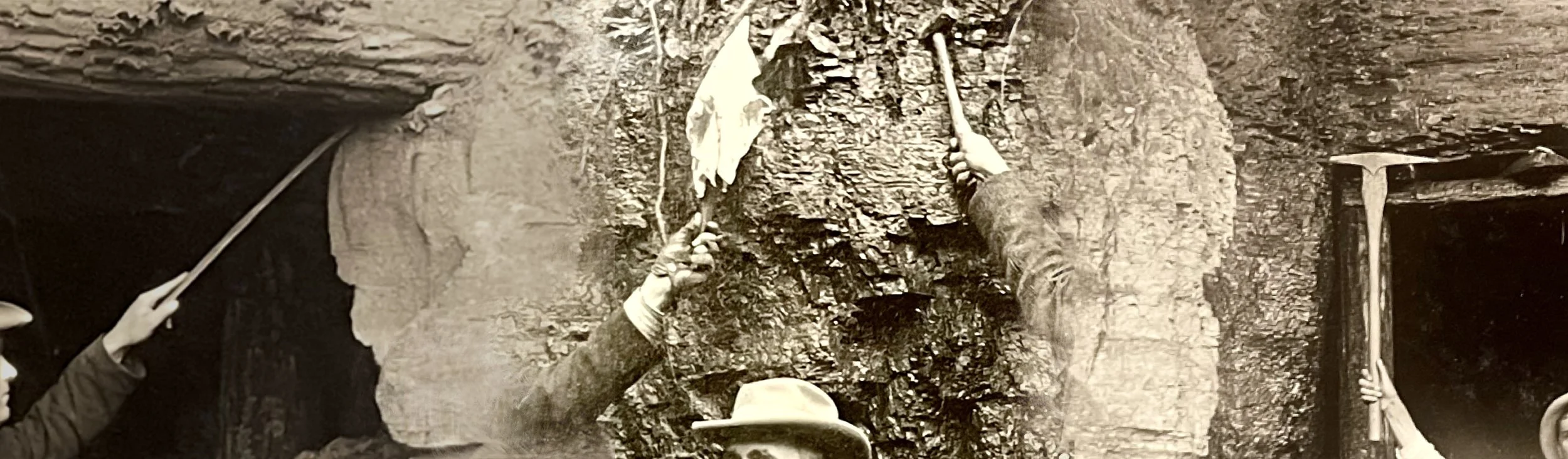

bituminous coal, Photo Curtsey of Allara Library, Pikeville Kentucky: Mayo Family, 1891, paper, digital projection, 12x10x8

In projected light, four women stand in a coal mine as beneficiaries of John C. C. Mayo, who introduced industrial mining to the American South. Elongated figures undulate over rippling paper, overtaking & permeating a precariously stacked coal wall.

In this installation, the Mayo family poses again; their gazes now emanate from the very same fossil fuel mineral that was the backdrop to their portrait when it was first captured in light in 1891.

-

By capturing the collapse of an abstract structure built by coal fragments, this photogram exposes expressions of systematic deconstruction. When burnt, coal creates light energy, and here, when burnt, its absence illuminates its presence.

Excavated from Eastern Kentucky in the United States of America.

-

Suspended fragments of refined bituminous coal are affixed in an industrial coal firing byproduct; cooled black tar. The coal delicately engages ambient light while the tar ground bounces glaring reflections that define her many gestural silhouettes.

-

Developed negative spaces draw light onto photosensitive paper, capturing coal forms and dried astilbe. The work endures the reality of ecological and economic forces bound to the source of a great power.

-

Suspended fragments of refined bituminous coal are irregularly fixed in the byproduct of a coal firing process; cooled black tar. The coal pieces reflect ambient light while drawing broken lines creating a luminous, sinking sensation.

Disenfranchisement and Aestheticized Poverty

As industrial mining continued to grow into the world's preferred energy source, working conditions and quality of life began to plummet in corporate occupied mining towns. (Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky, 2000)

Today, though coal excavation has generated marginal compensation for the workers, decades of mining still relegates the top producing regions to the bottom of most every quantifiable quality of life scale. (Fessler 2014), (Kentucky Quarterly Coal Report, 2019)

-

Small fragments of refined bituminous coal collect to from a permeable, circular wall around a swelling pool of tar.

“I recall a kind of democracy of experience brought on by shared economic status and shared location. When we moved to the city, the sort of raising of our own social mobility was very tied to the increased contempt for poor white people. I have always wondered about the ways in which oppressed and exploited people can turn against people with whom we should stand in solidarity.”

bell hooks, 2019

-

Burning Issues (Excerpt):

“By the time coal mining really cut its chops as a fully fledged industry, industrial mining beckoned the interest of a new party: United States military weapons manufacturing. Thanks to neocolonialism, by way of the broad form deed, The United States energy industry now had a tried and true internal proof of concept. A record and system of capturing regions to extort laborers and natural materials. By systematically targeting susceptible communities on the outskirts of the nation, a now thriving American energy industrial complex could expand land seizure to build weapons. The market viability for militaristic involvement was primed and ready, and wielded assurances to extend the nation's energy profile.”

-Austin Casebolt

Exchange Rate | 2022 | photo on board | 24 x 60

(1) Portrait of John C. C. Mayo, 1896 Available at the University of Pikeville in Allara Library Archives

Mayo’s family in Kentucky couture at the entrance of a coal mine, 1891.

Pikeville, Kentucky

Available at the University of Pikeville in Allara Library Archives

Burning Issues:

A Rise to Wealth

large scale mining practices have became more apparent in recent years. During the industrial revolution, bituminous coal became the preferred energy source upon an increasing demand for electricity.

Seemingly overnight, small mining operations turned into monumental industrial sites. As a result of this great and sudden expansion, extraordinary wealth grew from the advent of the unique black rock , and rural communities began producing labor as well as the precious energy that high society demanded be burnt.

Perhaps it was here where a paradigm emerged.

Early value exchanges of property and mineral rights created an avenue of opportunity for private and corporate entities to seize and simultaneously devastate mineral rich environments. Cunning acquisitions of small town digaries were merely a prelude to the vast injustices that tend to accompany corporate interests.

(1) Notable forefather - John Caldwell Calhoun Mayo (September 16, 1864 – May 11, 1914), American entrepreneur, educator, and politician. He is largely credited for the advancement of corporate property rights through land exchanges in Eastern Kentucky and Southwestern Virginia.

While working as a teacher in Kentucky, Mayo started collecting mineral rights from local homeowners in the area. Tales of his wife’s jingling change purse still linger on the breath of many Appalachian descendants. Families were quickly separated from their homes once Mayo discovered the wealth that rested rested beneath the surface of the land.

Folks around town can still remember how his wife, Alice Jane Meek, followed Mayo from behind. The couple announced themselves from door to door, and seduced the subdued by offering rare silver that matched the slickness of their tongues. She teased flickering coins to those who would strike a deal on the spot while Mayo preformed the con.

Mayo purchased land rights from the families and then turned around and resold the rights to corporate coal and iron manufactures for a significant profit.

Buy low and sell high. Classic.

& Everyone got bought out eventually.

Who could resist? Times were hard and things were bad. Sign here, take the money, and forget your troubles. Not to mention the unpleasantries of having a coal mine as a neighbor. It would be unbearably annoying to say the least.

Under a company umbrella by the name of the Paintsville Coal and Mining Company, Mayo seized entire communities in less than a year. Mayo accomplished this legal seizure by creating what is now known as the Broad Form Deed. This essentially gave Mayo legal permission to mine the acquired land beyond a typical residential need, and to simply sell not just the land, but its potential. (Big Sandy News, 1913)

Interestingly, the Broad Form Deed, in all its malleability as a legal tool, is still alarmingly effective at devaluing specific lives. A function that legal tools tend to conveniently permit.

Mayo specialized in central Appalachia. These strategic seizures established an entry point for big business. So much so that today, large scale mining is still being traded from company to company in the same mineral rich regions.

While it may be easy to say that he acquired the land rights through an agreeable purchase, the assumption that local landowners could have had adequate knowledge of the transaction impact on the community that would follow is less than realistic. Additionally, beyond any reasonable doubt, these families could not possibly have been aware of the monetary value that rested below the foundation of their homes.

John Caldwell Calhoun Mayo became a millionaire between 1888 and 1889 and ultimately the wealthiest person in the commonwealth of his time.

Unfortunately, for Mayo, injustice can sometimes flow upstream.

Mayo died in 1913 at the age of 49 of “poisoning”. Today, we would describe his cause of death as pneumoconiosis, also known as CWP/coal workers' pneumoconiosis.

His eulogy published in “The Big Sandy Press” noted his large contribution to the Eastern Kentucky landscape.

As for everyone else, Mayo’s land seizure process lives on, as well as his gallant contribution to a culture of want. To this day, his sales tactic are implemented as a tried and tru model for strategic disenfranchisement.

That model, co-opted by numerous ‘entrepreneurs’ around the country, became adjacent to the success of the energy industry for the United States at large. The Broad Form Deed, posthumously licensed (and sold!), became the coin of the realm for domestic neocolonization.

This form of the mineral rich land seizure by way of the Broad Form Deed, in its broadness, ripped open two distinct chasms that contribute to the formation of a new era; construction on morbidity. The era of an energy industrial complex.

1) a figurative chasm into the lives of the disenfranchised. The potential of accessible resources. Accessible wealth.

2) a chasm that most literally creates a deep fissure in the physical earth. The now perpetual excavation of minerals to be burnt.

Hollowing.

Emptying.

Gazing back.